Bill Cliftlands

The Anglican Churches

Whixall has five chapels! Five! Whixallites in the 19th Century were positively greedy for religion and salvation! But was it all ‘peace and harmony? That would be no. Was it ever?

The English Civil War (1642-46) was about what type of religion Britain should have – Puritan (nonconformist, anti-Anglican) or Anglican? A largely puritan Parliament won the war, but lost the religious settlement in 1660 – it was Anglican.

The Whixall puritan, Richard Sadler, immediately refused to go to church and was dragged with other Whixall puritans before the ecclesiastical courts in 1668. In the 18th Century, nonconformists tended to meet in licensed meeting houses, as at Higher House Farm in 1790. Only in the 19th century did serious chapel-building begin in Whixall. The Congregational chapels date from 1805/1870; 1829/1859 saw the building of chapels at Welsh End; Hollinwood chapels were built in 1854/1898 with Far End seeing building in 1859/1872.

But why so many? Was it just that Whixall was an endless expanse and people were fed up trying to reach chapel? No. One reason for the Anglicans winning the religious settlement in 1660 was that the nonconformists were so divided. The 19th century also witnessed this denominational conflict. So the ‘primitive Methodists’ of Welsh End did not agree with the type of worship practised at the Wesleyan Methodist chapels at Hollinwood and Far End. The Congregationalists didn’t agree with any of them. So they all built and expanded their own chapels.

Some evidence suggests that the first chapel in Whixall existed in the reign of Henry 1 (1100-1135) – beginning over 900 years of religious commitment in the Township. We cannot be sure, however, since the information came from a report on a lost document which had been ‘very difficult to decipher’. Other evidence suggests that there might have been just a single cross, that of Richard Scrupe, around 1256. Yet other evidence suggests that the chapel was in existence before the reign of Edward 1 (1272-1307), as early as 1201. Yet this date is itself uncertain, since the writer admitted difficulty in translating the document, including the date! Confusing! In 1424, a Richard of Whixall Chapel was named. We have more evidence for the Tudor period; there was certainly a ‘preste’ provided for in ‘Wycksayle’ early in the 16th century with a stock of cattle worth 32shillings provided ‘towards the maintenance of a priest to celebrate within the said parish.’ A subsequent petition to the Council of the [Welsh] Marches, although undated, would have been from 1586-1603 during the reign of Elizabeth I. The petition was to secure the return of lands lost to the chapel when the crown confiscated them on the accession of Edward VI. The land was needed in order to maintain a ministry at Whixall since Prees Parish Church was too far away. Religious Whixallites combined to contribute subscriptions in order to repurchase the land. Queen Elizabeth did respond positively to their petition. In 1655, the folk of Whixall paid £4 (c£1000 today, 2020) a year to support a minister while a piece of property provided an additional £40 per annum.

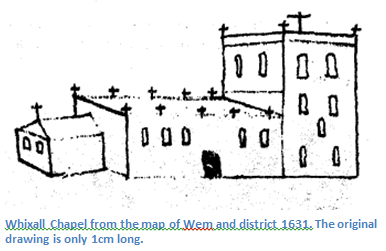

What did the first chapel look like? We have one image of the first chapel which appeared on a map of Wem in 1631.

While suggestive, it is not necessarily an accurate representation. Given the sandstone used to surround the second chapel, there is a possibility that the first chapel was built of this red sandstone (it would not have been built of brick).

What about the inside of the chapel? We know just a few things about a building which probably disappeared over 250 years ago. It is possible that two encaustic (painted) tiles that were found were from the first chapel. Two of the tiles had the remains of a coat of arms and it is one of these which suggests the date of c1201.

In 1655, Oliver Cromwell ordered a survey of all the churches and chapels across the land, and as a result, we have a brief description of the first chapel in Whixall. The survey stated that Whixall chapel was a ‘verie antient faire Chappell’. Inside, the chapel was ‘decently adorned’ with ‘wainscon’, in other words, wooden panelling at the bottom of the walls, as well as having ‘seates or pewes.’ It was not a small building since it was said to have served ‘above 400 soules’. It was the religious heart of the community: ‘the Word of God [being] constantly preached in the worst [of] these Disturbed times.’ This is referring to the English Civil Wars of the 1640s and early 1650s. We know that in 1608, the chapel had a new font. In 1852/3, seen as surplus to requirements, the chapel-wardens sold the same new font of 1608 (now described as the ‘Old Font’) to a ‘Mister Haris’ for a mere 5 shillings! (c£60). A report has noted that it was “octagonal and is ornamented with a scolloped shell, a lion rampant, birds, rosettes, and fleurs-de-lis’. Several signs suggest that the font had once been locked (had a lid) which is surprising in a post-Reformation font. Before then, in medieval times, font covers were always locked down in order to stop folk stealing the holy water. The holy water was regarded as precious, not because it was merely ‘holy’ but because people believed that holy water had magical properties that could prevent the dreadful effect of a neighbour’s curse or a witch’s spell.

Some remedial or improving work had been undertaken in the first chapel since a beam used in the second chapel had ‘1640’ cut into the beam. It is worth remembering that for most of its existence, the chapel in Whixall was Catholic – because everyone was – even in Whixall. It was only from the 1530s, with Henry VIII’s Reformation of the Catholic Church, that the folk who attended the chapel had to be Protestant – whether they liked it or not! While the first chapel was described in 1655 as ‘faire’, it was also described as ‘verie antient’. In the eighteenth century, it was to be replaced by a second, brick-built chapel.

We have little idea when the first chapel was demolished and the second chapel was erected, although the fact that it was constructed of 18th century brick gives us a very rough idea. The new chapel did not impress commentators. Bagshaw’s Gazeteer of 1851 describes it as ‘a plain unpresuming edifice of brick erected in the form of a cross…’ while in 1856, Kelly’s Directory described it as being ‘a plain brick building, with nave, transept, chancel, wooden turret and one bell’. Chapel-wardens’ accounts (1842 to 1867) give us some clues about the inside and the outside of the chapel. The chapel-wardens raised a rate on all inhabitants in order to maintain the fabric and services of the Anglican Chapel of St Mary’s. We know that the pews had floors and that two were altered in 1843. At the turn of the 18th century, at least some of them were owned as pieces of property. There was a benefactors’ board (white with black and red lettering) with money from Sarah Shockledge to be paid to the minister; this has now been placed in the present Church. The Chapel had a clock and a bell that was rung on Guy Fawkes’ night as well as for services. It had two stoves for which the chapel-wardens had to order coal. It has been suggested that the small, chunky altar table presently in the Sunday Schoolroom in St Mary’s Church came from the second chapel. The chapel possessed leaded windows. Outside, the walk was carefully maintained with 2s 3d being paid in 1845 for ‘[pre]paring and stocking the walk and picking the grass off it.’ In 1861, the path was gravelled. In response to a visitation in 1847, the chapel-wardens described the walls, floors and ceilings as being ‘clean & neat & in good order’. Significantly, however, the interior was ‘not free from damp.’ The roof was only ‘partially provided with spouting’ and there were ‘no drains.’ We know that the chapel was getting increasingly difficult to maintain. John Heath received 10s in 1843 in order to make ‘a Plan and specification of alterations of the Chapel’. Thus a ‘stone wall’ was built around the second chapel by William Lewis for £13. William Rogers received £6 13 10d for erecting ‘two iron gates & fencing’. In 1845, 30 feet of weatherboards with spars, nails, slates, and lime and hair were used to maintain the outside of the church. In 1847, however, the outside fabric was described as ‘slight and rickety.’ In fact, repairs on the chapel were made every few years; the major outlay before demolition in 1866 occurred in 1853/4 when £21 15s (c£2500 in 2020) was paid to William Powell and John Heath ‘for the necessary repairs of Whixall chapel and for the gate and access on the North side of the yard etc’.

What about the services held in chapel? The minister’s gown was washed regularly as was the chapel itself. A major cleaning occurred around the important Easter services. Inside, a velvet cushion and a cover were placed at the desk and the pulpit in 1846, almost certainly to welcome the new Vicar who had taken up his benefice in 1845, the Rev John Evans [The Rev Evans was also the domestic Chaplain to the Right Honourable Viscount Combermere]. As for music during the services, there was no organ but there was a village band, consisting of a clarionet, a viol, first and second violincellos, and a bass viol. The chapel sang in the singing pew which appeared to be a raised gallery. The choir was noted in the accounts from 1853 to 1866. In 1865/6, a vestry meeting agreed that £2 would be given to the choir for remuneration and £1 would be paid for choir books. Around 1862, it was suggested that the chapel might be replaced by another. While we know little about the origin of the second chapel, we know a lot about its demolition! Demolition began on 4 April 1866 (apart from the south transept which was used to house the parish hearse; see photocopied picture). The Rev Evans witnessed the very poor state of the Church noting ‘the fearful state of the walls.’ The chapel was so ‘rickety’ that the congregation was actually in danger; the singing gallery had been held up by an iron rod fixed under the front beam ‘to bind the walls together’ which when removed caused the gallery to break ‘by its own weight’ about six feet from one end. Its outside was ‘a mere shell of worm-eaten wood’. As we have seen, a key problem had been damp given the low-lying ground. Whixall’s second chapel was described as ‘being in a condition the badness of which could scarcely be exceeded’. Some argued at a clergy meeting that the ‘decay and damp’ made it ‘quite unfit for the sacred purposes for which it was consecrated, and to have rendered the present building incapable of restoration’. In other words, ‘nothing short of a new church’ would be enough. The collapse of the singing gallery had proven that!

(1867) The Third Chapel: this was built owing to the slow disintegration of the second chapel through the effects of damp caused by the low-lying ground and a failure to maintain the building in a way that might deal with that damp. However, the chapel was also built as a testimonial to the 20 years’ service of Archdeacon John Allen of Prees (b1810 Burton, Pembrokeshire, d1886) and a simple brass plate in the chancel acknowledges this. Ministers of the Church were willing to cough up – the Bishop of Lichfield provided as much as £100 (c£10,000 in 2020); the fund continued to grow ‘without any pressure’, not only by ministerial contribution but by subscriptions from Anglicans in Whixall and the surrounding neighbourhood until as much as £1,400 (c£150,000) had been collected. Work began. By April 1866, Whixall’s Chapel had been contracted for; the land up Church Lane (not suffering from damp!) had been donated by Whixall’s own Rev John Evans himself. Demolition of the second chapel had begun that April. Its bricks had been valued at £50 and were carried up Church Lane to be used as the foundation for the third, present chapel. In October 1866, it was noted that the walls of Whixall Church were ‘partly up’ but that the stonemasons were giving ‘much trouble’ because they had stopped work on the Church and had gone off to Cloverley Hall (in Calverhall) to do some work there instead!

At last, by April 1867, we hear that the new church was ‘all but completed.’ On August 29th 1867, a motion was put forward at the parish vestry to vote a sum from the Church Rates (not above £50) for the ‘conveyance and fencing of a proposed new Graveyard and Church site at Whixall.’ We know that the Church had been completed the following month, since on the 12th of September 1867, it was finally consecrated by Bishop Lonsdale. The opening of the Church in 1867 is celebrated by the brass plate to John Allen on the south wall of the chancel accompanied by a sampler of that year from a young girl of Tilstock Park. In 1894, Cranage, Shropshire’s famous ecclesiastical architectural historian, described the new church as ‘of brick with stone columns and dressings, and consists of chancel with north vestry and organ chamber, nave and north aisle of four bays, and bell turret over the entrance to the chancel.’ In a later, more detailed description, the brick is described as ‘Red brick (English bond) with sandstone ashlar dressings’. The style is described as ‘late Early English’. Its architect was said to be the famous Victorian architect G.E. Street. Before we get too excited however, we have to accept that Street may not have bothered with a tiny church in the wilds of northern Shropshire and probably just approved the drawings of one of his subordinate architects! As we have seen, £1400 had been collected towards the building of the third chapel. However, the true cost had been estimated at £1500. This caused real problems. For instance, the original plans were not met. The original plan (as can be seen in the photograph) had projected a fairly substantial bell turret that was to be made of brick. However, the present church has a wooden turret described formally as a ‘Lead-covered spirelet with louvred belfry at the east end’. The turret was already in trouble by 1900 when a bell turret fund had to be started. An entertainment was held in the ‘old’ or Church school in order to raise money to fix it. Fortunately, a new bell did not have to be bought. The bell from the second chapel, whose bell turret had become unsafe, had been hanging on a tree near the schoolyard of the ‘old’ school. The other consequence of the shortfall in money was that the Church was simply left unfinished. Since it would have been ‘an insult’ to build a church with any debt on it (according to the Anglican ministers behind the project), it was ‘thought better to erect the substantial part of the Church and leave the decoration for a future time’. We can only wonder what the congregation, and not the least, the Rev Isaac Allen, thought of that!

At a meeting of clergy and vestry (as late as November 1877!), celebrating Archdeacon Allen’s 30th year as archdeacon, the Bishop of Lichfield said that it had been decided that ‘as a practical proof of their sincerity, they should undertake the completion of the restoration of Whixall Church’. An additional £580 was raised. Surprisingly, the chapel did not even have a floor! An original piece of the flooring kept in the vestry tells us: ‘This floor was laid by W. Felton & W. Evans from Mr Price’s Coleham Building Yard, Shrewsbury, June 8th ’78’. We can only assume that pews and other furniture were added soon after the laying of the floor. Before 1887, winter evensongs would have been sung either in the dark or by candlelight. In 1887, however, lamps were put in place ‘which are Defries patent (see picture), each of 100 candle power.’ It was said that they ‘beautifully illuminated the whole interior with a soft yet brilliant light, more like the electric light than it is possible to obtain by means of any other lamp’. By 1936, oil lamps are mentioned again, together with a boiler and pipes although these would have been fitted much earlier. The chapel was given a fine brass lectern in May 1901 in memory of its redoubtable churchwarden, John Dawson, by his wife Elizabeth. The old font (described earlier) which had been kept in the second chapel for a while was moved to the present St Mary’s. The Benefactors’ Board is now on the north wall of the nave. Interestingly, according to the board, the church-wardens of Prees were to pay 10s every year to the chapel-wardens of Whixall for the poor. No, it’s not still being paid! The small, chunky altar table, also probably from the second chapel, has been placed in the Sunday School Room. The room was dedicated on 6th September 1992 to the memory of Rev Alan Holmes (vicar between 1957 and 1969) and Lydia Brown, headmistress of Whixall Church School for an incredible 38 years! It was erected by the late Charles Brown, church-warden of St Mary’s. Lydia Brown also gifted the Church a painting after Caravaggio of ‘Christ at (the supper of) Emmaus’.

Apart from the fact that the Rev John Evans contributed so much to the building of the Church, few of the vicars have left a particular mark on the interior of the Church apart from the Rev. J.J. Addenbrooke(1899-1934). In 1900, during his long time as vicar, he donated six striking Dore prints relating to the ‘life of Jesus’ and his teaching, three of which can still be found on the south wall of the Nave. The memorial windows to Addenbrooke were a colourful addition to the chancel; money was collected from a range of sources between 1937 and 1939 totalling at least £300. The money came from the Parish Church Council, the Church Fellowship, the Sunday School Festival, and even the Easter offering. Roll of Honour Boards for both World Wars are placed at the West End of the chapel. In more recent times, the work of the multi-denominational group ‘Whixall-in-Stitches’ has added considerably to the colour and decoration of the Church. The altar in the chancel is graced by an ‘All Seasons Altar Frontal’ stitched to celebrate the Millennium; it was embroidered by as many as 18 women from all denominations of the parish; an attempt was made to get as many people in the community to sew a stitch (under careful supervision, of course!). It was presented to St Mary’s on 8th October 2000 at the harvest thanksgiving service. A banner of the United Reformed Church also stitched by Whixall-in-Stitches was transferred to St Mary’s after that church closed. Whixall also has a number of colourful pew runners, kneelers, and cushions worked by Whixall-in-Stitches. One such celebrates the induction of the Rev David Baldwin, another, the service of his predecessor, the Rev Alan Bartlam. They feature a whole range of images from a tractor to a pig, to a canal bridge! The last effort by the group was a celebration of the names of clergymen who had served St Mary’s from its opening in 1867. Private individuals were also involved often stitching a memorial to a relation and Whixallite who had given much to the Church or the community.

Finally, that empty organ chamber. In 1900, an organ was purchased and ‘opened’ by the Bishop of Shrewsbury in the November of that year. The previous year had been spent raising the cash, for instance, with a Bazaar held in the ‘old’ Church school. Before electric power, the organ needed ‘blowers’ to provide the necessary air; apparently, it was a tough job for youngsters lifting open the spent bellows and it was a job that went unseen. But the organ chamber concealed other secrets than the labour of the blowers. A medieval church may well feature fascinating medieval graffiti. Less often do we find or take any notice of modern graffiti, yet St Mary’s graffiti is just as interesting in its own way as the medieval. There are a number of images – several outlines of hands, several gentlemen, a man on a bicycle, a man on a horse, a man with a cap, and a man with a hat, to name but a few. One graffiti message describes two young Whixallites as ‘idiots’ but the most important scratching reads thus: ‘Arthur Lyman 6 July 1919 Peace Celebrations.’ This reflects how St Mary’s has always been a centre of celebration in Whixall whether it was ringing the bell for Guy Fawkes Night or the celebration of Christmas or a White Wedding.

Whixall Congregational Church (now a private residence)

Without a single manorial authority; with many incomers taking advantage of this and the waste that was the Moss; and with the consequent growth of independent freeholders, it is possibly unsurprising that Whixall witnessed the growth of nonconformity: those who rejected the authority and tenets of the Anglican Church.

During the ceremony for the laying of the foundation of the second chapel in 1870, the Rev Evans spoke of the history of nonconformity in the area possibly going as far back as Henry VIII. The Whitchurch Herald in 1870 also noted that the general area was noteworthy as a place which had long rejected the authority of the Anglican Church due to the presence and preaching of two famous nonconformist preachers, Philip and Matthew Henry (see picture). In 1645 and 1646, during the English Civil Wars, Parliament dismantled the Anglican system of government and abolished the Book of Common Prayer. They replaced it with a Presbyterian system of government. Its implementation was very uneven across the country with Lancashire developing the most effective system. However, at least some of Shropshire appears to have operated the new Presbyterian settlement. Matthew Henry was ordained at Prees by the presbytery of Bradford North in 1657; he lived at Broad Oak on the Flintshire/Shropshire border. The Whixall nonconformist, Richard Sadler, was ordained in Whixall chapel (i.e. St Mary’s) in May 1648 (after returning from America after the wars) also by the Bradford North Presbytery; he signed Parliament’s ‘Testimony’ (a testament against religious error ensuring no return to the Anglican Church) insisted upon by the Parliamentarian government. He left Whixall but was ejected from the Church at Ludlow during the ‘Great Ejection’ of 1662 through Charles II’s Act of Uniformity of the same year which re-established the Church of England, but which Sadler (also) rejected. Sadler returned to Whixall in 1662 and was a natural focus for nonconformity in Whixall in the years till his death in 1675. Indeed, in 1668 and 1689, the Dean’s Court Book recorded a number of people who were taken to that ecclesiastical court for deliberately refusing to attend St Mary’s Church. Those named below may have supported Parliament in the Civil Wars, but certainly did not accept the new Anglican Church settlement.

Unsurprisingly, Richard Sadler is reported several times for not receiving Holy Communion according to the Common Prayer Book; others are criticised for this or for not attending the Church: George Causherock, Richard Madley, George Millington, William Benion, Richard Key, Joseph Heywood/Hayward and wife, Richard Higgins, Firmin Shaw, William Watkins, Arthur Ikin and his wife, William Truelove, and [Christopher?] Braine (almost certainly related to the William Braine discussed previously who died serving the Parliament in Jamaica). Sadler’s grandson, Dr Samuel Benyon, was born and lived in his house in Whixall ‘where he kept an academy.’ Benyon also preached at Broad Oak (the home of the two Henry’s) after Mr Henry’s death’. So we know that there were nonconformists – but was there a chapel?

When did the Congregationalists build an actual independent chapel? An abstract of a deed of 1706 acknowledging the title of Sir John Hill Bart and his grandson Rowland Hill Esqr to a small piece of land in Whixall which the Trustees (or Members) of the Dissenting Chapel in Whixall were to purchase proves that there was a nonconformist tendency in Whixall. It is known too that the Hills (surprisingly) were sympathetic to nonconformists. Despite the purchase of the land, however, it is not clear whether any actual chapel was built in the 18th century. 1790 sees the Congregational Church gathering for services not at a chapel building but at what was effectively a ‘meeting house’ at Higher House Farm which stood close to the future first chapel. It was also described as a ‘training institute’ for other would-be nonconformist preachers. Richard Everall was ordained minister for work at Whixall (as well as at Clive and Hadnall) in 1802. On 9th October 1805, at last, arguably the first chapel was opened. Everall offered prayers on the day. Almost the whole cost was defrayed by Thomas Weston, clearly a committed Congregationalist who believed that, as elsewhere, the Congregationalists of Whixall should have their own building. The chapel was well-regarded due to the pastor Rev Samuel Minshall’s, ‘holy Christian work in this neighbourhood.’ Samuel Minshall preached there from 1829 to 1861 and this longevity was acknowledged by the fact that the chapel came to be known as ‘Minshall’s Chapel’. As for the size of the chapel, according to Minshall’s Return to the Religious Census of 1851, it did not appear to be particularly small with 50 ‘free’ sittings and another 100 sittings. In addition, there was standing room for c50 if needed. On that day, the general congregation numbered c100 in the afternoon and 60 in the evening. This compared well with other chapels in in Whixall. However, the fact that the chapel was ‘inconveniently adapted for public worship’ and was ‘very small’ had made the worshippers determined ‘upon getting a structure wherein to worship with more comfort’, one that would be ‘more sightly.’ A Whitchurch Herald report of 1870 noted that it was hoped that a new building would be far more deserving of the name ‘chapel’ than the existing building.

The Whitchurch Herald carried a public notice of the laying of the foundation stone of ‘a New Chapel’ by Thomas Minshall Esqr of Oswestry in May 1870 (the stone was laid on 7th June). Contributions towards the erection of the building were requested and payments would be ‘thankfully received’ by Mr Massey of Tilstock Park, Mr Batho of Wood End Hall, Coton and the Rev E.K. Evans of Prees. It was hoped that subscriptions would be ‘eagerly forthcoming’ to ensure that the new chapel would not be weighed down by debt. Several Congregationalists certainly showed real commitment with considerable sums of cash. Thus Mr Thomas Massey (£100), Miss Massey (£50), Mr Stephen Massey (£20), Mr Joseph Batho (£100), Mr Dickin (£10), Mr Tudor (£10), Mrs Tudor (£10), Mr Maddox (£5) and the ‘Chesterfield Fund’ (£15. The Chesterfield Unitarian Fellowship Fund was begun in 1819) made contributions that allowed the building to go ahead. The ceremony for laying the foundation stone of the ‘New Independent Chapel’ occurred on the 7th June 1870. A hymn, readings and prayers were followed by Rev Evans who gave a short account of the history of nonconformity in the neighbourhood from at least as far back as ‘the time of the Henrys’ [Probably Henry VIII]. Next, a bottle containing contemporary newspapers was deposited as a time capsule. Thomas Minshall Esq. of Oswestry was presented with a ‘handsome trowel’ by Mr Thomas Massey on behalf of the church and congregation in order to lay the stone. Before laying it, Minshall spoke of his deceased uncle, the popular Rev Samuel Minshall. He also spoke of the ‘distinctive characteristics and tenet’ of Congregational Nonconformists, observing that Protestant nonconformists were compelled to be nonconformists due to the connection of the Church with the State. Yet they were not separatists and wished to ‘join in every good work with all Christian people’. A dedicatory prayer followed the laying of the stone and afterwards ‘a plentiful tea’ was provided in a tent. The Herald reported that the chapel, built and designed by Thomas Huxley of Malpas, would be ‘a neat structure, built of red and white brick’. It was to be built on the site of the old chapel of 1805. The opening of the new chapel took place in December 1870. The Oswestry Observer described the new chapel as ‘this pretty little church’ and further commented that ‘This building is considered, for beauty and convenience, a model for village chapels’. The Whitchurch Herald claimed that it was ‘one of the prettiest chapels – if not the prettiest chapel – in this neighbourhood,’ going on to describe it as ‘this exquisite little chapel.’ The style was Gothic ‘in full detail, ornamented with black-and-white bricks, with dressings of white Grinshill stone.’ Unsurprisingly, the building committee was said to be very happy with the new church. The church consisted of nave, apse, vestry, schoolroom, and porch. The Whitchurch Herald suggested that the restored old chapel could be seen as a ‘transept’. It was to be used in the future as ‘a Sunday School and for the purposes of tea and other meetings.’ The schoolroom was arranged in such a way that if needed, the opening of folding doors would allow the minister to have a full view of that room. A manse was erected close by as a residence for a minister; the Herald declared that ‘The whole buildings look exceedingly well’. The manse was extended for Rev J. Aston c1880 and paid for by Miss Massey. Three sermons graced the day of the opening. The church was so crowded for the evening service that Rev J.A. Macfadyen, MA., of Manchester, had to ask ‘the first congregation to retire’ so that he could give his sermon to the second congregation! The Herald noted that c230 sat down for at least one of the services with ‘all the denominations in this neighbourhood’ and folk from Whitchurch, Wem and many places beyond. Collections were made at the end of each of the three services. Around 450 sat down for tea; there were so many that it was ‘very late’ before the last received their tea.

The interior of the new Congregational chapel of 1870 was fitted up with varnished Bergen pitch-pine. The roof was described as ‘half-open being ceiled underneath the purlins, the lower part of the span being left exposed and varnished.’ In addition, the Herald reported that ‘The side windows are filled in with rolled quarry glass of a diamond pattern, and the circular in the front gable and Gothic window in the apse being filled in with enamelled glass of a chaste pattern’. In March 1917, the church was renovated. The chapel was alive to possibilities. In 1931, around 25 years before electricity arrived to light up Whixall, the chapel was able to use a nearby electric cable belonging to the North Wales Electric Company which ran from Whitchurch to Wem.

How was the chapel maintained? In the case of the renovation, a concert for fund raising was held in in the Council School with William Sutton as Chair. Congregationalists (unlike the Church of England which had previously benefited from tithes and church rates) had to build and maintain their own buildings and maintain their ministry from their own pockets from the very beginning. Chapels needed folk with deep pockets as we have already seen. Not only did Thomas Massey make a major contribution to the building of the second chapel but he also left an endowment of £500 with the interest to be used to support the ministry; Mr Joseph Batho left £600 for the same purpose. Some assistance could be in kind. Mr Ralphs offered to keep up the verges of the church grounds and did as long as he could. He also left £100 in his will. Over time, other endowments were made with the same purpose. Appealing visiting speakers such as Rev Newman Hall would provide a special service ‘on behalf of chapel funds’. Many came from Wem and Whitchurch to support the new chapel. The Centenary of the Church was celebrated in November 1890 and so the chapel was ‘tastefully decorated with flowers, fruit, corn and vegetables’. William Sutton was involved in this as well as providing a dish of plums. Unsurprisingly, a collection was made for church funds. In 1897, the annual church tea meeting was held and Mr John Evans, the treasurer, gave his financial report. He stated that the ‘income more than balanced the expenditure’; the balance being £20 4s 11d. The various departments of ‘the work’ were ‘in a prosperous condition’ and the officials were ‘cordially thanked’ for their services. Evans was re-elected treasurer, Alfred Edwards secretary, and the deacons were Mr Thomas Edwards, Mr Alfred Edwards, and George Forrester. Mr Sutton was elected representative to the Salop Association. In 1905, the Easter services took collections for ‘chapel funds’. Even when the new reverend, T.N. Oliphant, was formally greeted, a sale of fruit and vegetables and the like were sold to raise funds. The burial ground needed maintaining. The land had originally been purchased by William Sutton. In 1885, the Rev J. Thomas of Welsh Frankton visited to give a lecture on General Gordon ‘the great Christian general and hero’. The proceeds were to go to the burial ground. The Sunday School needed funding. In 1851, Rev Minshall reported that there were 20 Sunday School Scholars, but by the 1870s, numbers had grown to 60. In 1897, the choir and the congregation celebrated an ‘excellent supper’ on New Year’s Eve. After costs, £1 profit was made for the Sabbath School. Later, in August 1897, Sabbath School anniversary services were held with a collection taken for school funds. In 1900, the school had been successfully enlarged. It was in April 1900 that a bazaar was held to clear off the debt ‘for the school enlargement etc’. The opening ceremony took place in the afternoon with the pastor presiding. The bazaar opened with ‘the ladies of the congregation’ having ‘worked most energetically at the various stalls’, raising over £35. There was sufficient finance for the chapel to be rendered in the late 1920s.

The Wesleyan Methodist: Hollinwood (now in private residence)

The Wesleyans set up its first chapel at Hollinwood in 1841. Sometime between 1841 and 1861, as it was very close to the Congregational Church, joint services were held during Rev Samuel Minshall’s ministry. The services were held alternately at each place. The 1851 Religious Census showed that Hollinwood chapel was doing well since after just ten years 50 attended in the morning and 50 in the evening with 25 scholars in the morning and 23 in the afternoon; the average for the year was said to be the same. Clearly, some sort of Sunday School existed but a new one was erected in December 1885. Anniversary sermons on behalf of the Sunday School were given with a Mr Crewe of Horseman’s Green ‘an old favourite in Hollinwood’. The profits were such that the chapel could pay off the debt remaining on the new school. As with all chapels, Hollinwood had to pay its own way. In May 1889 annual sermons (in other words, they had been occurring every year) in aid of the chapel were held and ‘collections were very satisfactory’. At the end of 1895, rather progressively, a lantern and music evening was held with 100 slides elucidating the life of Christ with illustrated hymns thrown on-screen, verse by verse, to enable the choir and congregation to sing. The proceeds were ‘on behalf of the light and cleaning expenses of the chapel.’ The Herald in September 1888, reported upon the ‘beautifying’ of the church. Yet just ten years later, in 1898, a second chapel was built (pictured below). At first, just the repair of the chapel had been considered by the trustees. The fear that this would result in a mere ‘patchwork’ led to the building of a new chapel. At one meeting, Mr H. Manley observed that chapels in general were ‘badly lighted, badly ventilated and, he was sorry to say, dirty’. The total cost for the chapel at Hollinwood was projected to be £610-620; much had already been raised – for example, £292 had been promised and a tea meeting in November had raised £14. The foundation stone of the new Wesleyan chapel was laid by the Rev T.A. Allen on 23 February 1898. A large crowd had gathered in a field (given by Levi Green) from Whixall, Whitchurch and ‘other parts of the Circuit’ to witness the ceremony. The land benefited from ‘a frontage to the road’ and this was seen ‘as admirably adapted for the purpose and occupies a commanding position’. A further £110 had been received at the stone-laying, giving a total of £416. To name just a few subscribers: Jos Bowden, Mrs CH Williams, WH Smith (who was a partner with Wardle on the Mosses) and S. Green all subscribed £5 each; Josiah Williams, £3; Miss Lottie Green (£1), Master Frank Williams (£1), A. Hopwood (10s) and Mr Ainsworth (10s). At the evening meeting, the Congregationalist minister, W.E. Holt, spoke proudly of his ‘Congregational principles’; he also admitted to a ‘great admiration for the Methodists who had plenty of ‘go’ in them’. The Rev Thomas Allen ‘urged them to keep the Saviour’s fire aglow in the new place of worship, and the people would come in.’ A coffee supper was held a week later given by a few friends. About 40 sat down. A small charge was made and the proceeds were ‘devoted to the purchase of materials for the making up of articles for the coming of a bazaar in aid of the new chapel.’ Although no programme had been arranged, folk came with their party tricks, with solos sung by a range of people: Lottie Green, Annie Williams, Nelly Williams, Alfred Woodward and Herbert Maddocks to name but a few. The proceeds from a tea meeting of c200 in the ‘old chapel,’ together with 4 collections worth £15 10s 11, were expected to pay for the heating apparatus. However, the provision of the heating apparatus and other repairs in the autumn of 1901 cost as much as c£50. A chapel service in June acknowledged that ‘the liberality of the friends’ over the previous two years had been ‘severely taxed.’ Early in 1901, a debt of over £100 was cleared off the chapel property ‘with the generous help of a number of friends.’ Then immediately after that, it became necessary to repair and renovate the schoolroom at a cost of £12. To help defray the expenses, £5 15s was appropriated from Sunday School funds. In order to put the school in a ‘sound financial position,’ it was considered necessary to ‘make a special effort at the anniversary’. The collections exceeded expectations with ‘the handsome sum of £9 0s 9 ½ d.’ In addition, ‘Very kindly and generous support was received from the friends of the neighbouring chapels.’ As a result, the chapel was out of debt and a ‘satisfactory sum remains for the efficient working of the Sabbath School’. In 1907, the chapel was renovated and a new harmonium purchased with the Trustees providing £50 to cover the expenses. By the time the chapel was re-opened in May 1907, £30 had been raised by subscriptions and collections. And finally, previously, in November 1900, the Herald announced that the Hollinwood chapel was, on the 14th November1900, ‘duly registered for Solemnising, Marriages therein, pursuant to the Act of 6th and 7th WmIV., c85’.