The term Pre-history is classically used to cover ‘history’ that arises before written records. Typically pre-history is archaeological in nature with evidence derived from digs and excavations supported (and confirmed) by comparable evidence from other sites; or via scientific investigations such as radio-carbon dating.

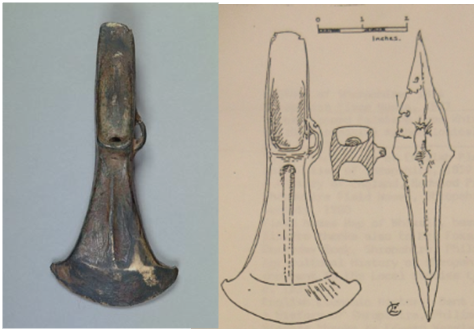

The first evidence of an apparent human presence in Whixall came via the discovery of a looped bronze palstave (axe-head), which was found by George Saywell (of Moss Cottages) in 1927 (1).

This axe was reported as being of ‘fully developed Middle Bronze Age type’ and was dug from an approximate depth of eight foot from an area to the east of Oaf’s Orchard (believed to be bed 13.8). Dating of this axe head, using information from other sites, places it within the period 1500-1200BC. [The axe-head is held within Shropshire Museum, Shrewsbury]

Supporting this human presence is information from radiocarbon dating of plant and tree pollen from peat samples (2). Samples taken from the Moss dated to the period 1280-760BC and indicated a period of sustained agricultural activity at this time. This then would have placed our axe-yielding individual in a working agricultural environment between, as a minimum, 1500-760BC.

Conclusive evidence of human presence came first from 1867, revealed from police investigations in 1889(3), that two turf-men Henry Simpson and Thomas Woodward ‘came across’ the remains of a youth in a sitting position partially covered by a leather apron embedded in turf lying near a three-legged stool. The finding of the stool is without precedence with respect to ‘bog-body’ finds and, record has it, that it passed into the possession of Rev J Evans (Vicar of Whixall). The youth was reburied in Whitchurch.

In c1875-76 George Heath discovered the remains of a young woman (only 300 yards from the 1889 find). There is no further evidence of this find other than she was re-interned at Whitchurch.

The final, documented, body found was on Tuesday 7th September 1889 when Henry Slack and Thomas Parsons (possibly on bed 12.2) found bones at a depth of 4.5 feet. The bones turned out to be of a 40-50 year-old male, bearded, and just short of 6 foot tall. He was found lying full out face down and was without clothing and, bizarrely, both feet and a bone from the lower leg were missing. Retrospective stratigraphic pollen analysis, taking into account the depth of samples and the depth at which the body was found, places this individual from the period of Early-Middle Bronze Age (2100-1850BC).

Once removed he spent some time in a coffin at the Waggoners Inn before being re-buried on the Thursday in a Whixall Churchyard (‘new part of Whixall churchyard near a stump on the left of the entrance’). The discovery of the deceased in each case was such that the coroner of the time considered that no advantage was to be gained by holding an inquest and, as such, no foul-play was deemed to have occurred.

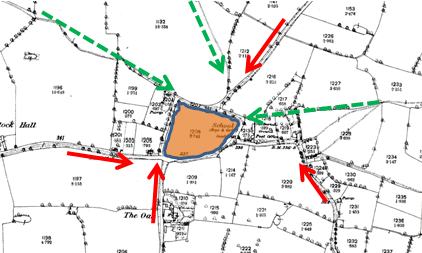

These three bodies and the palstave indicate that human activity was present in Whixall (on the Moss somewhere between Olaf’s Orchard and the moss-end of the track down to Moss cottages) [see modified GoogleEarth image below] around the period of the early part of the Bronze Age. No further evidence of human remains has been found locally although, tantalizingly, a turf-man is credited with giving information that dug-out canoes had been found (4); but of this there is no evidence.

The Romans, responsible for bringing civilisation to Britain, first arrived in 55-54BC but didn’t actually take sufficient control to rule until 43AD. They then governed Britain for the next 360 years. Although taking up residence across much of Britain there is no evidence of them getting any closer to Whixall than Bettisfield, to the west, and Alkington, to the east.

When the Romans departed, Britain entered a period of turmoil called the ‘Dark Ages’. The Celts of England fought each other, as well as the invading Saxons, and neither of these groups subdued the Welsh Celts. King Offa (757-796AD) ruled the Saxon kingdom of Mercia (containing Whixall) and it was he who built the dyke to keep the Welsh at home. Whixall was probably very much ‘frontier country’ between marauding tribes from either England or Wales. Out of all this though arose the Anglo-Saxons – who were to become the precursors of ‘the English’. They advanced as pioneers and settlers, cut clearings in woodland, developed the plough creating agriculture, and started villages and homesteads which can still be traced today.

Taking evidence from:

- the Domesday Book: “In Saxon times it was held by Aeldid who was a freeman”

- archaeological interpretation of the landscape: a typical settlement can be an irregular circle, partly enclosed, with fields, tracks and open pasture radiating from its centre (see map) and

- the historical interpretation of place names (5): the origin of Whixall is ‘Hwituc’s Halh’ where ‘Hwituc’ is an anglo-saxon name and ‘halh’ means corner, angle or remote nook

we can draw a creditable conclusion that, of substance, Whixall started its historical life as an anglo-saxon farmstead belonging to Hwituc; and that this occurred sometime after 613AD (and before 1066)(6).

Map showing the seven points of access to the ’roundabout’, either by foot or track. The field used to have a stream running through it, now culverted, and would have been suitable as a ‘green’ for enclosing cattle. This field is marked as Roundabout on the tythe map.

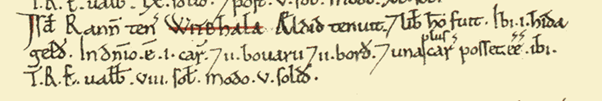

The first historical, written evidence of Whixall is from the Domesday Book of William the Conqueror published in 1085-86 (7). In its original form (as can be seen) it is highly abbreviated medieval latin, with some vernacular terms defying interpretation. From the best translation of the latin we get:

The Domesday Entry for Whixall

Ranulf also holds Witehala (Whixall). Aeldith held it; he was a free man. One hide pays tax. In Lordship one plough, 2 ploughmen, 2 smallholders; one more plough would be possible. Value before 1066 eight shillings, now five shillings.

It is interesting that in this translation of the Domesday Book that Aeldith is a man. In 1986 Parker (6) translated Aeldid to Aldith, a woman, whom B.L. Edwards considered was the Queen of England (8).

In brief: Harold was the Saxon King of England and had Manors including Whitchurch. Edwin, Earl of Mercia owned, amongst other Manors, Bettisfield, Dodington, Malpas and Worthenbury. In 1057 Edwin’s sister Aldgyth (also spelt as Aldgid /Aldith; who owned three Manors around Whitchurch) married Gruffydd, the King of Wales. Gruffydd died in 1063 and Aldgyth married Harold to become the Dowager Queen of Wales and also the Queen of England. In 1066 after Harold’s death she fled abroad via a short stay in Chester.

All of this puts Whixall well and truly on the map but, because of its poor potential for profit, it consistently remained and remains in the shadows of history.

References: (1)Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society vol 47, pt1, 1993; (2) Radiocarbon vol7 p205, 1965; (3) Turner RC & Penny S, 1996, Three Bog Bodies from Whixall Moss, Shropshire. Trans Shropshire Archaeol Hist Soc. 71. pp.1-9; (4)Transactions of the Offa Field Club 1929-30, page 38; (5) Ekwall, E., 1960 Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names (4th Ed); (6)Parker, C. 1986 Domesday Book, Shropshire; (7) See http://opendomesday.org/place/SJ5134/whixall/