Bill Cliftlands

It’s hard to believe but education was a divisive issue for Whixallites; for reasons of class, religion and every day necessity. Most folk did not see that it had any relevance to their daily grind, their labouring to live through chill winters and wet summers. Besides, until 1891, education was not even free! Religious bodies were critical in the arrival of education in Whixall.

The nonconformist divine Dr Samuel Benion (1) undertook his ‘Grammar Learning’ with a schoolmaster based in Whixall in the 1680s who was doubtless a nonconformist himself. But few wanted such learning or could afford it. As for Anglican schooling, land was assigned to the churchwardens of Whixall in 1708 ‘for the benefit…[of] the schoolmaster there’; he was paid 30/- which was 10/- more than the curate! Between 1734 and 1747 (at least), Whixall churchwardens did pay schoolmasters to undertake schooling in the parish; ‘Robart Jaxson’ was paid 5s several times for ‘scoling’ in 1734 and 1735 and appears to be schoolmaster in 1746 when he was paid 12s 6d quarterly (worth about £133 today, 2020), an increase from 1734. In 1747, one Tagg and one Bromfield were paid nearly £2 for providing ‘schooling’. Learning was being taken seriously by the Church. Unfortunately, we have no idea who was receiving this schooling. Intriguingly, the Tithe Map of 1847 (2) shows a School House Field – had a schoolmaster once lived there?

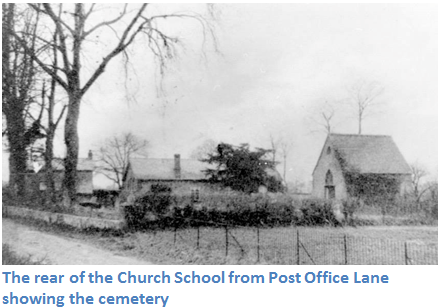

However, not everyone shared the passion for education if it was for someone else’s child. In 1836 an attempt to provide for the schooling of ‘six poor children’ to be ‘selected by the Minister of Whixall Chapel’ fell through when a piece of land to fund the education fell to heirs who were not obliged to pay it. There was no school building at this time. However, a project for the building of an Anglican school had been planned in 1845 with the arrival of the new vicar  John Evans and in 1847 he purchased a site and ‘a house for a master’ (Possibly the site shown on the Tithe map). In the end, Evans contributed personally an extraordinary £272 7s 6d (c£28.5 thousand in 2020) towards the total cost of £652. We know that he was interested in education; he had been Second Master in the Free Grammar School in Whitchurch and he wrote several works for schools. In 1849, the Salop District Committee of the Lichfield Diocesan Education Society granted £50 ‘in aid of the New School and School House now erecting at Whixall’ and for ‘fitting up [Evans’] New School at Whixall.’ The government’s own Committee of Council on Education granted £150; the remainder came from ‘private subscriptions as well as the sale of trees growing on the site’. All of these organisations and individuals contributed to the erection of the Church school in 1850 – and so in effect, built our present Social Centre. But this was an Anglican school and its purpose was made very clear:

John Evans and in 1847 he purchased a site and ‘a house for a master’ (Possibly the site shown on the Tithe map). In the end, Evans contributed personally an extraordinary £272 7s 6d (c£28.5 thousand in 2020) towards the total cost of £652. We know that he was interested in education; he had been Second Master in the Free Grammar School in Whitchurch and he wrote several works for schools. In 1849, the Salop District Committee of the Lichfield Diocesan Education Society granted £50 ‘in aid of the New School and School House now erecting at Whixall’ and for ‘fitting up [Evans’] New School at Whixall.’ The government’s own Committee of Council on Education granted £150; the remainder came from ‘private subscriptions as well as the sale of trees growing on the site’. All of these organisations and individuals contributed to the erection of the Church school in 1850 – and so in effect, built our present Social Centre. But this was an Anglican school and its purpose was made very clear:

‘promoting the education of the poor in the principles of the established Church’. It may have been provoked by other new builds – nonconformist chapels at Welsh End (1829) and Stanley Green (1805) making concrete the growth of nonconformity in Whixall and providing competition for hearts and minds. Unsurprisingly, a predominantly nonconformist township might not wish to send their children to the Anglican school so non-Anglicans in Whixall sent their children to ‘Miss Green’s Private Adventure School'(3) in Hollinwood and to ‘Miss Foxe’s’ as well as to a Wesleyan School in Hollinwood (built sometime after 1854) . This difference over education was to intensify and serve to cut Whixall in two.

1891 was the year of the (Whixall) Civil war! Why did it erupt?

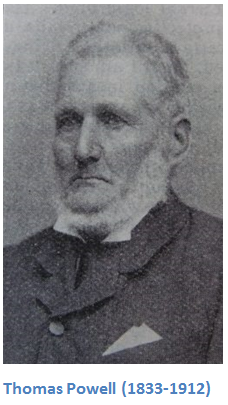

It was over the building of the present Whixall Primary School at Brownsbrook and explains how that very important building exists today. The accommodation at the Wesleyan school in Hollinwood (building no longer exists) was declared to be inadequate. The Wesleyans had to extend it or suffer its closure. It was rumoured that the soon to be vicar of Whixall, the Rev (JJ) James Jennings Addenbrooke (b1859), owned the land needed for any extension and had refused to sell any part of it to allow for an extension. These rumours were lies. Addenbrooke did not own the land, but the lie was out there. Still the school could not be extended and an order was made for the school to be closed. Parish meetings were called, the first in Prees (Whixall was not an independent parish at this time and was part of Prees as a chapelry) and the second in Whixall. These meetings were explosive because both sides were fighting for the very ‘souls’ of the children of Whixall – as well as to educate them. Edward Addenbrooke (b1816, father of JJ), the Vicar of Prees, wanted to build a second Church school and use it for missionary purposes! Thus the nonconformists would have no school at all and their children would be educated as Anglicans. The first meeting was held in Prees; Edward Addenbrooke as the senior cleric was appointed chairman. The platform contained only Anglicans (such as John Dawson and Phillip Phillips, both St Mary’s Whixall churchwardens) – not a single nonconformist was given a place. The two camps were clearly separated at the meeting, with the Anglicans placed above! The meeting lasted as long as two hours and saw ‘animated discussion’ with views being expressed ‘very warmly’ according to the Wellington Journal. This is, of course, code for a very angry meeting indeed. A resolution was passed calling for a second meeting in Whixall itself proposed by the leader of the nonconformist cause – Richard Butler (b1809), a Wesleyan Methodist of Hollinwood. The second meeting was structured in a way similar to the first – with all the Anglicans on the platform together with a token Congregationalist, the ageing Rev John Aston. This meeting proved even more tempestuous than the first, and the Whitchurch Herald left its readers in no doubt as to the nature of the meeting. It described a ‘lively discussion’ which contained ‘expressions of a personal and unpleasant nature’; indeed, the journalist reported that the exchanges were ‘so warm as to be impossible to hear what was said.’ At last the ‘Whixall people’ spoke and Richard Butler (Wesleyan Methodist, Hollinwood),  seconded by Thomas Powell ‘of the Welsh End’ (Primitive Methodist, Welsh End), proposed that an unsectarian school be built (i.e. not Methodist or Congregationalist or Anglican) with a committee elected by the ratepayers. The nonconformists, who earlier in the century had acknowledged their differences by building their own chapels, now came together to build a school. The Anglican counter-attack was swift. An ‘amendment’ was proposed by the Whixall Anglican minister, Rev J.J. Addenbrooke and seconded by churchwarden John Dawson, which aimed at securing a ‘branch Church School’. More apparent skulduggery followed with the Chairman Edward Addenbrooke declaring the amendment carried – without a count. Butler and Powell demanded a count but ‘great confusion’ followed and the ‘Church’ resolution stood. The Chairman immediately declared the meeting closed. One can only wonder how many thanks Edward Addenbrooke received on his customary ‘vote of thanks’. The stage was set and the war of words was to continue…who was going to build the second school in Whixall – the Church or the Chapels?

seconded by Thomas Powell ‘of the Welsh End’ (Primitive Methodist, Welsh End), proposed that an unsectarian school be built (i.e. not Methodist or Congregationalist or Anglican) with a committee elected by the ratepayers. The nonconformists, who earlier in the century had acknowledged their differences by building their own chapels, now came together to build a school. The Anglican counter-attack was swift. An ‘amendment’ was proposed by the Whixall Anglican minister, Rev J.J. Addenbrooke and seconded by churchwarden John Dawson, which aimed at securing a ‘branch Church School’. More apparent skulduggery followed with the Chairman Edward Addenbrooke declaring the amendment carried – without a count. Butler and Powell demanded a count but ‘great confusion’ followed and the ‘Church’ resolution stood. The Chairman immediately declared the meeting closed. One can only wonder how many thanks Edward Addenbrooke received on his customary ‘vote of thanks’. The stage was set and the war of words was to continue…who was going to build the second school in Whixall – the Church or the Chapels?

So who did build the second, ‘new’ school in Brownsbrook in 1891? Angry Anglicans or aggrieved nonconformists?

Bitter rivalry over the building of a second school spread throughout the township like wildfire. Scurrilous rumours were rife. Thus the lie about the Rev. J.J. Addenbrooke’s ownership of land in Hollinwood. The lie that if a Church school was rejected another school would be built at extortionate cost to Whixall ratepayers. The lie that a majority of Whixallites (who were nonconformists!) wanted a Church school. During the furore, one Anglican clergyman had made a false accusation against a leading nonconformist (possibly Richard Butler of Whixall) and had been forced publicly to withdraw his allegation. It really was getting dirty.

Edward Addenbrooke, Vicar of Prees, and the prime mover on the Anglican side, lost no time in pursuing a second Anglican school given that the Wesleyan school was to be closed. He applied for a grant from the ‘Board of Education for the Archdeaconry of Salop’ in order to build his branch ‘Church’ school. His reasoning was clear – it would place the school in an area “almost wholly given over to Dissent [i.e. nonconformity]” – in fact, only about a quarter of a mile away from the old Wesleyan School! He had also swiftly begun to secure subscriptions for the new school. But the nonconformists were arguably even quicker off the mark. The main player here was Richard Butler of Moss Farm in Hollinwood but he was only one of many leading nonconformists who met together for the first time at Welsh End chapel. They organised themselves into a group of 12 trustees and a grand committee of 36. What was important about this organisation was that it contained all the chapels in Whixall – Congregationalist, Primitive Methodist and Wesleyan Methodist. The township of Whixall was c75-80% nonconformist and so the weight behind the committee was considerable. But it was the focus that the committee provided that was critical. In just a week, £180 in subscriptions had been received and a site purchased from William Forrester. Architectural plans drawn up two years before (and already approved!) were immediately sent for approval again from the Education Department. Again, no time was wasted in asking for tenders so that ‘the building will be proceeded with at once’. George Dodd of Whitchurch won the contract. Indeed, the Wellington Journal of the 23 May reported that the foundation stone had been laid. The Anglicans had lost. The laying of that foundation stone had dashed all their hopes.

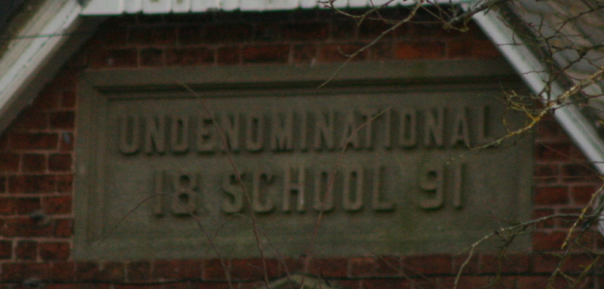

The present Whixall Primary School in Brownsbrook was being erected as an ‘Undenominational School, see picture’. Yet the verbal bile did not end there. Edward Addenbrooke had a fierce exchange of letters with Richard Butler in the Whitchurch Herald and the Wellington Journal each defending their own positions and accusing each other of misleading statements. Butler also had a pin-ball letter exchange with the Rev John Lee of Tilstock who did own the land that the managers of the now defunct Wesleyan school had hoped to extend into. In the end, the Editor had had enough of both of them and simply ended the angry correspondence!

What lay behind all this vitriol? Surely, the ‘old school’ for the Anglicans and the ‘new school’ for the nonconformists was what Whixall needed. But if this is so, why was the community so divided?

Obviously, fundamental to the division was religious belief; for both, schooling was partly a matter of salvation, of going to heaven. Whixall Anglicans saw the nonconformists as ignorant and godless while Whixall nonconformists saw the Anglican Church as too hierarchical and elitist. For instance, the Whixall Congregationalists of Stanley Green believed that power lay with the congregation not with a bishop; Whixall Congregationalists chose and paid for their minister. In the Anglican Church, it was a wealthy landowner or a high clergyman who appointed the minister. The Rev. Edward Addenbrook, the Vicar of Prees, was the man who appointed his son, J.J., to be Vicar of Whixall (both educated at Oxford University) since he had the right of presentation to the living at Whixall. R.T. Smith, a prominent Methodist from Whitchurch, made the division clear at the laying of the school’s foundation stone. He blamed ‘the Church party’ for ‘all the upset and trouble’, trouble caused by ‘overbearing persons in the township’. He claimed that the Church party intended to ‘crush the Dissenters’. The violent terminology is indicative of heated feelings. But the division in Whixall was not only about national attitudes towards religion – it was also about national politics. Rev J. Aston (Whixall Congregational Chapel) declared triumphantly that by securing an ‘Undenominational Schoo’l, they had ‘…raised aloft the flag of religious and civil freedom’ and in the future they would continue the fight for ‘liberty of conscience’.

This religious division was not only true of Whixall – it was true across the United Kingdom. This strength of feeling was the result of nearly 100 years of history in which nonconformists struggled to gain equal civil rights; nowhere would this have been more important than in Whixall. Nonconformists were only allowed to hold parish office (such as constable or overseer of the poor) from 1828; an 1836 Act allowed chapel ministers to hold marriages and an 1880 act finally allowed nonconformist ministers to take burial services. This represents the fight for civil equality. This took great nonconformist commitment; it was the sort of commitment that led H.R. Lander, the Liberal candidate for North Shropshire, to congratulate the folk of Whixall “upon the[ir] indomitable pluck, perseverance and independence’ in securing the ‘Undenominational School’ school. In a particularly astute comment, he observed that ‘the Liberals of Whixall were independent, because they had land of their own’. Whixall was divided politically. Anglicans, such as John Dawson and the Rev J.J. Addenbrooke, were members of the Prees District Conservative and Unionist Association, while nonconformists such as Richard Butler (Moss Farm), William Sutton (Rose Cottage), William Darlington (Whixall Hall), Jos. Ikin, William Forrester and T. Powell, were all prominent Liberals and, coincidentally, represent a roll call of those who secured the ‘Undenominational School’. Yet Whixall was a predominantly Liberal township in the 19th century and Conservative outposts such as St Mary’s Church and the Church School were small islands in a sea of nonconformity. As for the day that the ‘Undenominational School’ opened, the Whitchurch Herald concluded that “The day indeed was a red letter day in the history of Whixall, and especially satisfactory to the Nonconformist body.” It was not a red letter day for the community of Whixall, however. Resentment continued to smoulder. At the annual feast of the Oddfellows Club at the Waggoners in 1892, J.J. Addenbrooke, the Vicar of Whixall, lamented the fact that ‘there was no nonconformist minister present’ as was usual at this major community event. The rumours, lies, misunderstandings and sense of grievance lingered in Whixall for many years to come.

- Samuel Benion, born Whixall 14th June 1673, educated Whixall and Wirkworth, Derbyshire. Graduated Glasgow University as its first Doctor of Medicine.

- According to the accompanying notes to the Tithe maps field 343, School House Field, was owned by Alexander Samuel Duff Esq.

- Private Adventure Schools; where the use of the word ‘adventure’ is in the sense of risking a (financial) loss as these schools, also known as Dame Schools, were typically elementary schools run by widows run for private profit. Often these schools were initiated “out of necessity to enable the ‘poor women/widows’ to stay one step ahead of begging”.

Moving on……

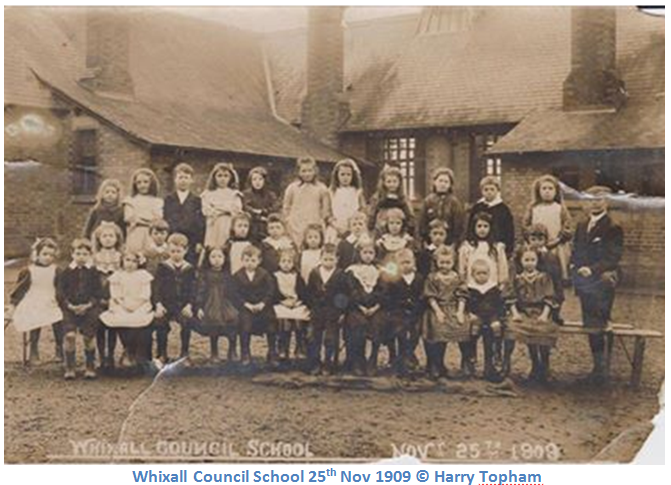

The ‘Council’ school (the present Church of England Primary School and Nursery) was a lively school often with over 140 pupils on roll in the 1890s/1900s including infants and juniors. Football (a ball was bought in 1899) was played by the boys in a field adjoining the school provided by Meredith Evans of Bostock Hall. When the headmaster, Ainsworth, tried to find a field in which to play cricket in 1900, he could not find one suitable; cricket was never mentioned in the log books again.

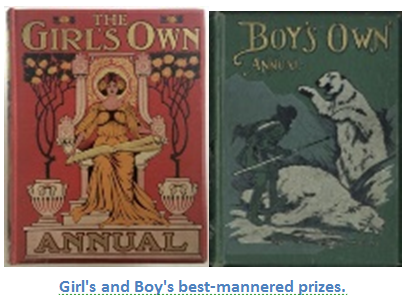

By 1900, the school did have two swings. In 1908, we learn that it was the boys themselves who ‘collected and subscribed enough money to buy a football’. A school treat was held in Evans’ field in 1901 where football and rounders were ‘entered into with zest’. In the evening, the children were given a treat of nuts and oranges. Christmas was obviously the time for real fun. Ainsworth bought a magic lantern with the precise aim of ‘entertaining the children’. The tea and lantern entertainment ‘was successful beyond our expectation and gave great pleasure to the children’. It must have seemed like magic in 1894! Tea, oranges, nuts, sweets and biscuits were handed out annually at Christmas time. In 1892, the second Christmas after the opening of the school, a Christmas tree was purchased. In 1896, the pupils ‘had a dip into a bran tub in which was placed a variety of toys’. The Lantern entertainments continued with two men boxing causing ‘roars of laughter’. In 1897, the slides included 50 illustrating a ‘Trip to Australia’ as well as ‘panoramic and effect slides’. Apparently, the screen was 12 feet square. While children were allowed in free, parents paid and this money was used to pay for the oranges and nuts and the like. The 1898 lantern entertainment lasted three hours (!) and the slides were ‘heartily enjoyed’. In 1901, the lantern ‘entertainment’ was on the Boer War. The charge for adults was 6d and the money raised – 50shillings (about £60 today) – was to be used to pay for ‘the new Acetylene Gas Generator’ (i.e. the lantern). The Church School (the present Social Centre) also had its ‘Christmas Tree Party’ – and in 1906 a tree ‘almost touching the roof’ was erected ‘beautifully decorated with toys, candles and ornaments.’ ‘Smiling faces and pleasing remarks’ greeted the tea itself. When the desks were cleared away, an entertainment of 29 items provided by the children followed. These included songs and recitations and particularly the singing of the school song ‘Be true’. Many prizes were distributed, not only for attendance, but also for ‘progress, conduct, fellowship, and manners’. The ‘good fellowship’ prizes were decided by the votes of the children and were won by Nellie Powell and James Eccleston. Lily Davies and Wilfred Bradshaw won the most coveted prizes for the best-mannered boy and girl – the Boys’ Own Annual and the Girls’ Own Annual! Garments, toys and sweets were presented to all the children. The children had a lot of fun at Christmas.