Liverpool to Whixall;

the memories of a Second World War evacuee.

Sarah Tabuns (nee Jewell), together with her brother and sisters, was evacuated to Whixall to escape the expected bombing of Liverpool Docks and Harbour. She remembers this time with much happiness and joy and thanks all the people of Whixall who took them in as their own and looked after them. This is her story.

It has been almost 77 years since the Second World War entered my life. I was a child at St Gerard’s School Kirkdale, Liverpool, and I was evacuated, together with my brother and sisters, to north Shropshire – a place called Whixall. It was to be my home for the next three and a half years. This is my story of that time.

The declaration to war for the United Kingdom was made by Neville Chamberlain on 3rd September 1939 at 11.15am. But we knew it was coming. From August of that year air-raid shelters were being constructed in the streets and back-gardens to protect us from the bombing which we knew would come. This was Liverpool – the largest port on the west coast and extremely important for our convoys from the west.

At school we were all issued with our ‘Micky Mouse’ rubber gas-masks and had to carry them everywhere, always. We practised daily putting them on and taking them off. At home my younger sister, Ellen, about one-year old, had a full body mask and mum was instructed on how to place Ellen inside; something Ellen did not enjoy and it always made her cry loudly. Sometime later we were told that we were to be evacuated. We were being moved from Liverpool to a safe place in the countryside, which was all very exciting. We would all be going together, older sister Mary (thirteen), me, Sarah (ten), Bridie (eight) and younger brother John (six). Mum was told to pack a pillow-slip for each of us, which was to contain our clothes and anything else we needed. Mum would stay in Liverpool with Frank (three) and Ellen.

Operation Pied Piper was scheduled for the 1st of September, the mass evacuation of children to places of safety. So, on that Friday morning, we set off to school, with our pillow-slips over our shoulders, and there we lined up ready to be taken by bus to the train station. All our relatives were there to see us ‘off’ and we felt as though an adventure had begun. We also thought we would be coming home again fairly soon.

Our first destination was the small Shropshire town of Wem where, on arrival, we were given a shopping bag full of food which was to be given to our future carers to help with our board. We were then loaded onto more buses which took us five miles deeper into the Shropshire countryside. Journey’s end was the small and rural village of Whixall.

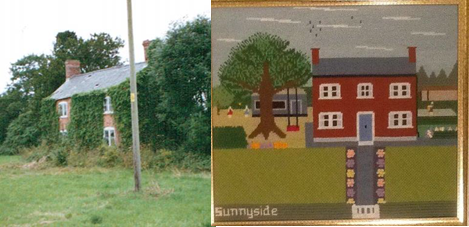

On arrival we were directed to the church hall where we were given some refreshments. Afterwards we all sat in our little family groups out on the grass outside; we were unsure as to what would happen next. It had been a long day. A volunteer from the church approached us, Miss Preston, and she asked if Bridie and I would like to come and live with her. It was only to be us two as she didn’t have room for Mary and John (we didn’t know where they would end up). Miss (Sarah) Preston then went back into the church hall and we waited outside until our names were called. While we waited other children who had come with us were taken (somewhat sadly in some respects) from door-to-door to be chosen by the person who lived there. For us the Vicar took us in his car to Miss Preston’s house – Sunnyside, Hollinwood – where she lived with her brother, who we were told to call Mr Ted.

As we walked along the path leading to the front of the house, the vicar pointed to some plants that were growing on the right hand side. He asked if we knew what they were – we didn’t. They turned out to be beetroot, something we had not seen before. On the other side of the path the ground was covered with grass and growing there were four or five apple trees, whose branches were bent low to the ground with the weight of the apples. Plums were also plentiful. For the rest of that first day and evening we explored what was, to us, a big property – they even had chickens.

As we walked along the path leading to the front of the house, the vicar pointed to some plants that were growing on the right hand side. He asked if we knew what they were – we didn’t. They turned out to be beetroot, something we had not seen before. On the other side of the path the ground was covered with grass and growing there were four or five apple trees, whose branches were bent low to the ground with the weight of the apples. Plums were also plentiful. For the rest of that first day and evening we explored what was, to us, a big property – they even had chickens.

Soon it was the end of the day and time for bed. Bridie and I shared a room which was very cosy. It faced west and we had no light in the room – except for a candle which we could light for a small while. I read my book in bed, probably a volume of ‘Just William’, which I did until the sun set and I could no longer see the words. It was now time to sleep.

From the day we went to live with Miss Preston, her work load was doubled. There was no electric in the home, no gas, no stove to cook on, and no running water. There was a pump outside and this is where she filled containers of water to be carried inside. During the Winter the water would freeze and a fire had to be built around the base of the pump to melt the ice in order for us to be able to pump it. On wash day the water was carried into the back kitchen and each container of water emptied into a huge multi-fuel boiler in which clothes and bedding were boiled. Mr. Lus, Miss Preston’s brother, who owned a shop near the canal, had an electric generator; presumably to keep some of the things he sold fresh. During the winter Mr Lus and his wife delivered bread to the customers (rather than them coming to the shop). They would come into the house with the bread, and I then recall that either Bridie or I would warm their gloves in front of the fire before they moved on to their next delivery.

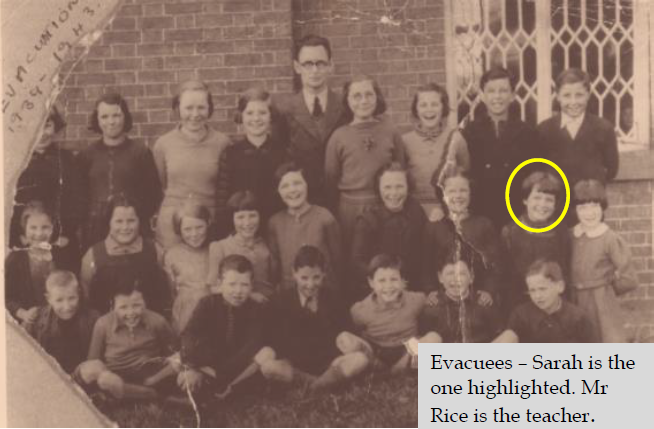

Our whole school of St Gerard’s, teachers too, was evacuated to Whixall. There were so many of us that we had to be divided into two local schools. Mary and John went to the Council School, together with our teacher Miss Lee, (still present as a school and now called the Whixall C of E Primary School) and the Church School (St Mary’s, no longer operating but with the buildings still being used locally as the Social Centre) which Bridie and I, and our teacher Mr Rice, went to. Because we stayed in different homes and went to different schools the only time we regularly saw Mary and John was at Sunday Mass which was held in the Church Hall.

Some days after our arrival we were all gathered together in the school closest to where we lived. It seemed quite a long way to walk there (about a mile each way), but we got used to it. Our ages ranged from five years old to almost fourteen and I think our teacher, Miss Lee, must have found it difficult to teach such a variety of ages all in the one class. This was strange for us. Back in Liverpool, with more pupils, we were taught by grade but here in Whixall with fewer children they were all taught together in one class. Strange now, but seemingly not so at the time, we were separated from the local school-children and taught as our own group. We didn’t routinely play with the local children, which was by design rather than inclination. At school we had too much news to swap with our contemporaries from whom we had been separated overnight, or at weekends, and, in the case of Bridie and me, locals living near Sunnyside were either too young or too old to make happy play fellows – Gwen Jones and Clifford Clorley were “teenagers”. I do recall sharing time with Joyce, who had a bicycle, who we used to walk home together with from school.

Some days after our arrival we were all gathered together in the school closest to where we lived. It seemed quite a long way to walk there (about a mile each way), but we got used to it. Our ages ranged from five years old to almost fourteen and I think our teacher, Miss Lee, must have found it difficult to teach such a variety of ages all in the one class. This was strange for us. Back in Liverpool, with more pupils, we were taught by grade but here in Whixall with fewer children they were all taught together in one class. Strange now, but seemingly not so at the time, we were separated from the local school-children and taught as our own group. We didn’t routinely play with the local children, which was by design rather than inclination. At school we had too much news to swap with our contemporaries from whom we had been separated overnight, or at weekends, and, in the case of Bridie and me, locals living near Sunnyside were either too young or too old to make happy play fellows – Gwen Jones and Clifford Clorley were “teenagers”. I do recall sharing time with Joyce, who had a bicycle, who we used to walk home together with from school.

We took our lunch to school, usually a sandwich, the favourite being chocolate spread. I can’t remember what we brought to drink, but many children brought cold tea in a glass bottle. Sad to say, but probably typical in a child, I don’t recall much of the school day which couldn’t be summed up by three words – reading, writing and arithmetic.

At school one day we were recruited to the war-effort by a lady from Bostock Hall who asked whether we would like to knit something for ‘the troops’. It was things like pullovers or gloves or other items that would have been useful. I volunteered to knit a V-neck pullover. The pattern and wool were supplied. Unfortunately progress was slow and I had returned to Liverpool before it was finished (I do hope someone else finished it off). We also volunteered to go on door to door collections – during school hours which didn’t do much for my education – collecting scrap paper and tin cans to help with the war effort. We collected it all up and took it to a barn at Bostock Hall where it was stored before being collected again and taken off.

Also to help with the War effort we decided to put on a play. I unfortunately don’t recall the story-line but I do remember there was much singing and dancing and I wore an organza dress that Miss Preston had given to me. The play was a success and was shown at both schools and, with the teacher’s permission, we charged an entry fee with the money collected being sent off to Mrs Winston Churchill. Before the money was sent we had to write a covering letter to send with it, and I was chosen to do this. In return I had a letter of thanks, long since lost, from Clementine Churchill thanking us for our efforts and donation.

Most of the entertainment in Whixall took place in its churches. There were concerts and plays, socials and, of course, church services. Sunday was a very busy day. In the mornings we went to Mass which had the added opportunity to meet our siblings (who attended the other school remember) and in the evenings we went with Miss Preston to her church. I remember from these services that as we were leaving the Vicar would shake hands with everybody, including us children.

Once a year the church held what they called a Garden Fete. Miss Preston always had a stall there and in the weeks leading up to the Fete people would come to the house leaving all sorts of donations for sale – articles they had made themselves, jewellery, and just about anything they thought would sell. Bridie and I would love looking through all the collection of things that were left. On the day of the Fete we would both go with Miss Preston to help, I usually volunteered to go round and sell the raffle tickets. We really enjoyed the Garden Fete.

We didn’t really know where Mary and John ended up in the days after our arrival but one day we set out to look for them. More by luck than judgement we ended up walking past a house with an open door. Inside we saw Mary who was in a long dress turning a handle on a machine we had never seen before. It turned out to be a machine for turning milk into butter. John was here too, with Mary, and we were all happy to see each other. I don’t recall where this house was exactly, but it seemed a long way from where we were living.

Mary didn’t stay long in Whixall as she was sent back to Liverpool to help mum with Frank and Ellen. At the time evacuation was only until one reached the age of 14, schooling finished then and so it was a ‘return’ home to find a job. My stay was for three and a half years, Brodie stayed for five – so much for our short stay and a quick return home.

Much of my spare time was spent reading, I loved it. Many was the time I could be found laying on the grass under the apple trees reading a book – and occasionally reaching up for another apple to eat. There was no shortage of books to read as, in the parlour, there was a glass book-case that was filled with books, many of which the Preston family had won as prizes at Sunday School. It was filled with books from top to bottom and I remember one book in particular – a very large bible that lived on the bottom shelf.

During my stay the best part of the day I really liked was in the evening, just when it was beginning to grow dark. Miss Preston would draw the curtains, light the oil-lamp, and I would settle down with a book. I used to continue my reading in bed but I couldn’t do that during the winter months as we had no light in the bedroom. We would light a candle long enough to get ready for bed, and then it would be blown out. Candles were in short supply. Besides the magazine from Lus’s niece (who was staying with him helping in the shop while the war was on) the other source of much desired reading would come from Mr Ted. He would arrive home after his five-mile motor-cycle ride from the farm in Whitchurch bringing with him the ‘Daily Mirror’ newspaper. He would pass it on to Bridie and me and I would immediately go to the ‘Quiet Corner’ section of the paper to read the poem by Patience Strong. There was one in the paper every night and they were very good.

Another reading pleasure was my weekly delivery of the magazine ‘Girls Crystal’. Every Friday we would stand by the front gate patiently waiting for the postman to arrive on his bicycle. Every week would be a parcel from home loving wrapped in brown paper by Mother and tied up with a bit of string. We would carefully undo the string and unpeel the brown paper (so that it could be used again) which was a trial in patience as we couldn’t wait to get to the Holland toffee bar we knew would be inside. This bar came in squares and we would carefully divide it out before we ate it. Sweets were rationed so this toffee bar was always a special treat. Inside the parcel was also my Girls Crystal and a letter from home bringing us news.

It was such a simple life for us, with the war seemingly miles away.

Mother came to visit us when she could. If father couldn’t make it make it, nanny would often come with her. Mary would stay at home looking after Frank and Ellen. On Sundays there was a bus from Liverpool bringing several sets of parents to Whixall. To come on any other day of the week it was by train, and then only to Whitchurch, resulting in a five-mile walk to Whixall. On one occasion when Nanny came with her and I remember us all sitting in the parlour while Bridie played the organ. Miss Preston had an organ which Bridie was allowed to play. She took to it right away and could play almost anything by ear. She started to play the hymn which she had just learnt ‘Art thou weary, art thou languid’. This was probably not a good choice as, almost certainly, Mother and Nanny would have been very tired from the long walk to the house from the bus-stop. The only thing I could ever play on the organ was ‘God save the King’.

Although I don’t remember being homesick, the day before my Mother arrived, I would stare at the arm chair where I knew she would sit, and keep thinking with excitement ‘tomorrow my Mother will be here’. After they had been and gone, I would look at where she had been sitting, and think sadly, ‘yesterday my Mother sat there’. She would ask if we wanted to come home, we would say no, so she wouldn’t worry about us.

When Mother visited, Miss Preston would provide dinner. Since food was rationed it wasn’t easy to find extra food for visitors. My Mother would respond by bringing sugar that she had saved which would then give Miss Preston enough to make jam with the damsons and other fruit from her trees.

I learned later that my mom, with Frank and Ellen, had also been evacuated. They ended up in Salisbury but mom didn’t like being away from home so she didn’t stay long and returned to Liverpool. By now the air raids on Merseyside docks and harbour had started and mum must have found it so difficult moving two small children into the air-raid shelters which, at night without lights, must have been particularly difficult.

We also had another source of information from Liverpool. My best friend Dolly, who lived in a house on the way to school, her mother knew my mother as they had both gone to school together. So, when Dolly’s mom was due to visit we would meet her off the bus and she would tell us all that was happening as we walked back.

Sometimes after parents had visited children would become homesick, even asking that their parents take them home. This wasn’t such a good idea since air raids were taking place, bombs were being dropped, and people were spending long hours in air raid shelters.

I recall that we were growing up fast, literally. The clothes that we had brought with us were becoming small and tight. Replacing clothes was no easy task. Apart from Betty’s samples, (see later), we occasionally got samples of clothes from home. These parcels would be sent to school with our names on and must have been paid for by mum. Among some of the clothes for me I remember was a horrid purple rubber raincoat. I hung it on the back of the door and avoided wearing it at all costs. However, the day came when, with heavy rain, wearing it seemed unavoidable. When I removed the coat from its hanger is was a stiff as a board. Examined more closely it was obvious the rubber had perished and the whole garment was no longer wearable, and certainly no use as a raincoat. Although now without a raincoat I was happier that the purple rubber one was no more.

Shoes were another problem. Mother tried her hardest to find me some that would fit. One pair she sent had higher heels than I usually wore and I loved them, but they were too small. We arranged to send them back and Miss Preston advised that I should also ask for ones with a lower heel which would be better suited to all the walking I had to do. To my delight the replacement pair were of the same style of shoe in a larger size. They not only fitted but still had higher heels. Bridie was still at a stage when she would happily wear whatever she was given – no problem with heels for her.

I don’t think Miss Preston approved of my shoes, or at least the size of the heel, or a hat that I had been given, called a Halo hat. It was called a Halo hat because it was worn on the back of the head creating a halo effect. Mine was a dark brown colour made of felt. On one occasion I wore it to go and watch the boys milking the cows. One of the boys, in a moment of frivolity, directed a stream of milk at me covering my felt hat with lots of milky spots. Try as I might I could not wash these spots out and they remained for the duration I had the hat. A hat I and Brodie both had which Miss Preston did approve of was our straw hats. These we only wore on Sundays to go to church. When we got back they had to be carefully packed away, which is where they stayed until the following Sunday.

Just around the corner from us were our friends Ivy and Dora Taylor (sisters and fellow evacuees). They lived with Misses Annie, Fanny and Alice (all Williams). Alice ran the small shop on Platt Lane. Sometimes, when invited we would go around to their house to play board games, such as snakes and ladders, and occasionally Miss Annie would come to visit Miss Preston bringing Ivy with her. The three of us children would then amuse ourselves with pencils and paper. We also did a lot of singing, with Misses Annie and Preston having to decide who the best was. I remember Ivy always used to sing Danny Boy.

A letter from home one Friday was to bring us some thrilling news. Mother wrote to tell us we had a new baby sister, Phoebe. Excitedly we asked if Mother could bring her to Whixall so that we could see her. Sometime later, and with dad having some time home from the RAF, they took the train to Whitchurch. They walked the five miles to reach Sunnyside, with mum arriving with a hanky wrapped around her feet helping with the blisters that had rubbed up on her heels. I can still ‘see’ them now tired and weary – and they still had to walk further to where John was staying to show him his new sister. Needless to say a long and exhausting day, with them both sharing the carrying of Phoebe, was enough for them to hire a taxi to get back to Whitchurch and the train home.

Looking back now I think of how fortunate we were to be staying with the Prestons. Like ours they were a big family too. Not only was there Miss Preston there was Mr Ted. Mr Ted was musical and played a small trumpet called a cornet. He would practise a lot as he played it in church on Sundays. He would often offer it to us to try and play, but neither of us could get a sound out of it. He also had a lot of sheet music and Bridie and I would often spread it out on the parlour floor, spending hours singing each song as we laid it down.

Then there was Sam, and his wife Kate, who were market gardeners that I visited every Saturday afternoon, and Lus who had the shop near the canal who I used to visit to get our milk. This walk was a pleasure as they had a niece staying with who helped serve in the shop. She had the luxury of a subscription to a magazine, the name of which I cannot recall, which she passed on to me when she had finished with them. This was a supply of new reading which kept me entertained.

Then there was Jack who, despite losing a hand in an accident, ran a paint shop, did a lot of carpentry, directed funerals and, when required, provided a taxi-service.

Outside of Whixall there was Harry and his family. They owned a garage in Nantwich but would always come and see us every Sunday. Brodie and I would set off walking down the lanes to meet them which, when we did, they used to give us a lift back in their car. Often, when the bombing was bad they would stay an extra night before returning home. Betty and her family owned a manufacturing plant in Manchester making children’s clothes. Many times the ‘samples’ were passed down to us as were the toys from their son. Then there was Annie. Annie was a live-in nurse who stayed with her patients in their homes. Sometimes she would come and stay with us when she was ‘between patients’. She liked to ride her bicycle and would often take me with her to explore the surrounding countryside.

The nearest town, Whitchurch, was five miles away. Mr Ted worked on a farm there and travelled to and fro by motor-bike. For us you either, walked, rode a bike (if you had one) or went on a Friday, when it was market day in Whitchurch, and there was a bus. When we went with Miss Preston I remember her taking us into Fulgoni’s café. Once inside and seated they would put a plate of fancy cakes in front of you, and you only paid for what you ate – that was a real treat. The downside to these trips was that Miss Preston and I suffered from motion sickness so, by the time we got home we were not feeling very well. Needless to say a trip to Whitchurch by bus was not our favourite, but the cakes made it worthwhile.

At some point in time another school was evacuated to Whixall, (St. Malachys, Toxteth, Liverpool, now closed) and, once again, the good people of Whixall found homes for them all. I remember a particularly large family who were all evacuated together, their Mother came with them, and they were given a small house all of their won to live in. Even with this influx of children the number of children at the Church school was dropping so, when one of the teachers left, being called into the RAF, we were all transferred to the Council School. We, as a family, and pupils from St Gerard’s were now all together.

As much as we liked this ‘new’ school the one thing we really missed was ‘our garden’. Next to the Church School was a piece of ground which was divided into plots. Two children then shared a plot and, with the help of local adults, grew lots of extra vegetables. Of particular help were Mr Bishop, who lived next to the school, Lydia Brown (nee Bishop) our headmistress, and our own teacher Miss Lea. They would all buy seeds and share them amongst us for us to grow. We were proud of our achievements, especially when we took them home to show Miss Preston.

When I arrived in Whixall I couldn’t ride a bicycle. However, walking home from school with a local girl called Joyce, who owned a bike, I learnt to ride using her bike. I could set off easily enough but would stop simply by riding into the grass bank and falling off! I learnt how to fix a puncture in the inner tube and learnt all about the lights and using the bell. It was war-time and the lights had to be dim so the bell was used to warn people you were coming. If your lights stopped working you had to walk – the police were very strict over bells, lighting and walking.

One day Miss Lee (a teacher from Liverpool who lived next door to us with Mrs Hall) told me that, if I could get hold of a bicycle, there was a newspaper round that I could have. I wrote home to ask Mother if I could have a bike. I was both surprised and delighted when she said I could, and she agreed to get me one and would send it by train. In the meantime Miss Preston loaned me her bike to deliver the newspapers while I waited for ‘my bike’.

Every night after school I would walk to Prees railway station taking short-cuts over stiles and across the fields – a round trip of about 2-3 miles. The station-master got to know and expect me and, for what seemed like ages, my arrival would be greeted by a shake of his head, telling me it hadn’t arrived yet. I lost count of the amount of times I dejectedly walked the, seemingly, longer route back. Then, one day, on entering the luggage area, I saw it a label on a bike with my name on it. The bike was wonderful, it was a racer with dropped handlebars, almost touching the ground, white, with narrow mudguards covering the wheels. I rode home that day and started to deliver the newspapers using my own bike. I even used it to fetch the milk from the shop with the milk-can dangling from the handlebars.

Happily I didn’t need the services of a doctor during our stay, but poor Bridie did, she really suffered with ear-ache. She always seemed to get it during the night and she would wake up crying. Miss Preston would get up with her and take her to sit on the stairs where she would sit and comfort her. The doctor came to visit Whixall every so often setting up a temporary surgery in the house of a neighbour who lived opposite. There would always be a long queue of people waiting to see him when he arrived.

I remember having ‘tummy troubles’ on occasion which confined me to bed. Miss Annie (Preston), the nurse who stayed with us ‘between patients’, usually gave me arrowroot at the time to ‘settle my stomach’. It always seemed to do a good job, as I was better and out of bed in no time.

Upon reaching the age of fourteen, school leaving age when taught education ceased, one had to return home. About this time I started to feel it ‘was right’ for me to return and with mother’s consent I returned to Liverpool. Packing up all my belongings in a suitcase that Miss Annie supplied I went off (with a few others returning) to catch the ‘Sunday Bus’, the bus that had served to transport visiting parents over all the years we had been in Whixall. This bus would take me direct to Liverpool. At the other end of the journey I got off in a dark and unlit Liverpool. Carrying my big suitcase I had to make my own way home. The street gutters were filled with large water-laden iron pipes that were positioned to provide much needed water following the on-going German bombing of Liverpool. Stumbling along with my case and avoiding the pipes where I could I eventually reached home. Much had changed.

I still had another four months to do at school until I was fourteen so I had to enrol to attend school. At school I didn’t know anyone, and they didn’t know me; many of my previous friends were still evacuated. It all felt very strange. However, children being what they are, I soon made new friends and, as much as was possible, my life became ‘normal’.

In later years whenever I met others who had been ‘on the evacuation’ we would swap tales and stories of our years away. I remember one tale, told by a woman who was an only child, being evacuated with her best friend, also an only child. On their departure their mother’s had told them ‘whatever happens stay together’, and so they did. When they arrived in Whixall and were paraded door-to-door for rehoming the woman who opened the door at one pointed to her friend and said ‘I’ll take that one’. They both immediately cried out, and probably cried, saying their mothers had told them to ‘stick together like glue’. It was a measure of the generous people of Whixall that this lady relented and took them both in.

I have to say that although it was sad to leave our homes to avoid the air-raids , it was a wonderful experience. The people of Whixall took us in, complete strangers, gave us a home and cared for us as we grew up. The Preston family took unlimited care of Bridie and me, and treated us as their own. Yes, we misbehaved as young children do, and Miss Preston would often say ‘I’ll write to your mother’ but she never did, and we’d behave (until the next time). I would like to say thank you to all the families of Whixall who took us in and looked out and after us, but personally, especially to the Preston family who made my ‘evacuation’ a memory I fondly look back on.

Following the Second World War Sarah Tabuns (nee Jewell) moved to Canada with her husband to find a new life. Now, having had two sons and a happy life, she reflects on her time in England – particularly during the war when she and her brother and sisters were evacuated to Whixall. Her memories of this time have been compiled and have been added to the Whixall History Group website at: www.whixallhistory.co.uk/

If anyone can add further details to Sarah’s story we would be happy to hear from you. Email <whixallhistory@gmail.com>