In September 1066 William I (aka William the Conqueror) invaded England to claim the throne; he was crowned on Christmas Day in London. In 1067 he returned to the continent, where he spent most of his reign, having made arrangements for the governance of England in his stead. On one of his visits back to the UK the ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’ states:

Then, at the midwinter [1085], was the king in Gloucester with his council … . After this had the king a large meeting, and very deep consultation with his council, about this land; how it was occupied, and by what sort of men. Then sent he his men over all England into each shire; commissioning them to find out “How many hundreds of hides were in the shire, what land the king himself had, and what stock upon the land; or, what dues he ought to have by the year from the shire.”

This then was the Domesday Book and it was all about determining all /any taxes to be paid to the Crown.

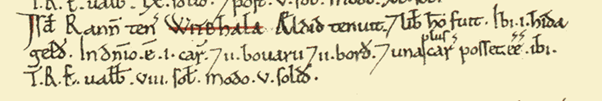

The Domesday entry for Whixall translated gives: Here there is approx. 120 acres of land taxable. On the land attached to the Manor there is one plough/ ox team with two ploughmen, eleven herdsmen, eleven pheasants and two smallholders; and one more ox-team might be employed. In King Edward’s time (pre-1066) the Manor produced an income of eight shillings per annum and now it produces five shillings”.

Clearly at the time Whixall was not a tremendous asset to the Crown, 120 acres of taxable land is a mere 0.1 squares miles.

The next assessment of land-holding resulted from the Tithe survey of the 1840s – following the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836. A tithe was one-tenth of annual production of harvestable crop or livestock, or personal gain, which was payable to the rector of a parish. Typically this had been paid in kind by the product produced but there was a move to levying all of this by coinage – real money changing hands. Commissioners surveyed all landholding, converting in-kind tithe payments to monetary tithe-rent charges. Effectively the Commissioners were undertaking the same sort of inventory that the Domesday Book chroniclers had done. This gives us a very good breakdown of landholders /owners in Whixall (see section on Tithes and Landholdings).

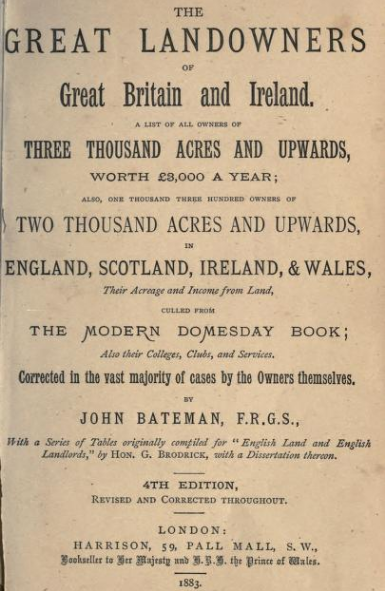

In 1861 the National Census indicated that the whole of the United Kingdom was owned by just 30,000 individuals for a population of 20 million. This was disputed and questioned and together with a change in landholding – smaller properties consumed into larger ones, proprietors able to purchase under “40-50 years’ purchase holding” and increased use of tenure, leasehold and freehold it was difficult to ascertain who exactly held land. So, in 1872 local government boards were ordered to complete a list of landowners from all individuals /companies /trusts etc paying rates. The result was the two-volume “Return of Owners Land, 1873” edited by John Lambert now called the ‘Modern Domesday’. Following on from this was the four-volume “The Great Landowners of Great Britain and Ireland” (aka The Acre-Ocracy of England which reads like a Who’s Who) edited by John Bateman and published between 1876 -1883. This work looks at all individuals owning land to a total of 3000acres or more, or with a valuation giving more than £3000 annual income.

The return for Salop from the 1873 edition gave:

248,111 people living in 50,804 houses from 254 parishes. 7,281 owners held land of <1acre and 4,838 of land >1acre. The total extent of land was 791,941 acres with an estimated rental value £1,484,833.00. There was considered to be 19,675 acres of waste or common land (the mosses combined take up c2000acres). From this it is impossible to determine who held land locally, the listing is just name, place of residence, landholding and value. Individuals could live outside Shropshire and still hold land within it.

Modern technology now uses the internet and the site https://map.whoownsengland.org/ attempts to show current landowners. The map below shows a screen grab from the site.

There is very little in the public domain revealing land-ownership.